I walk into your house. I’ve done that several times since you’ve been gone but each time before, Earl sat on his couch watching TV and Richard walked in with me. Today I walk in alone. I need to say goodbye to the heart of this home.

Where I used to see your smile greet me are tables with your memories spread out, professionally organized and price tagged. The fine wood cabinet that you loved sits in the television’s spot. Your recliner and the table beside it that caught all your necessities are gone. I stand in the doorway forcing my memory to put you back. It works. I smile a lopsided, sad grin.

With the drapes finally open, the light brightens the room but pushes you deeper into the past. I always wondered why you never opened them, and what the room would look like if you did. Now I see but it’s one more sign that you’re gone.

I’d call you when I was in town. “Is it OK if I stop by?” I asked, already knowing the answer.

“Of course, honey. I’d love to see you.”

“I’ll be there in ten minutes.”

You’d say, “Take your time. You know where I am.”

But today that’s not true.

Instead I look at all your precious memories plucked from decades of storage. Soon a parade of strangers will decide if Beth’s tin dollhouse is worth what they’re asking, pulling apart and cherry-picking Earl’s baseball card collection and oohing and aahing over your treasures as though walking through a museum.

You lived here for all those years, slowly accruing what is now yellowed and fragile. You were content to be among the accumulation of belongings of your five children and things that kept them fed, warm and entertained. You guarded your things with the ferociousness of bird guarding the nest long after the fledglings flew on their own. When age robbed you of your vision and it came to your mind to handle a souvenir of your life, and couldn’t find it, you’d lament its loss even though it was still exactly where you placed it. We couldn’t find it. You weren’t very good with specific details we needed to locate it. You’d wave a hand, “Oh, on that shelf over there.” In the kitchen? Dining room? “Never mind,” you’d say with the countenance of one heading to the gallows. “Someone took it.” We’d let it go. We had no choice. We wanted to help but couldn’t. You’d mourn your loss and we mourned our loss of you leaking away.

I walk upstairs. I enter the first bedroom. Stacked on a bed lie neatly folded stacks of quilts that once upon a time covered your children. Richard told me of seeing his breath on frigid winter mornings and hating to get out from under those very quilts. I think of the minutes and hours that added up to days of your life cutting and sewing scraps of material together, compensating with fabric for the heat you couldn’t afford.

It makes me think of what we do with the thousands of moments between birth and death. How we spend our time. How curious is that word, “spend,” as though we are given a millionaire’s amount of minutes at birth to use any way we choose.

We spend oodles of minutes simply growing up. That’s eighteen years out of only God knows how many. During those years, though, a portion is both spent and invested. That’s what education is.

After that, it’s our choice to spend or invest our minutes. Too many of them we use to chase fleeting sensations of pleasure or gaining nothing but more things to pack in boxes when we move. We create children, spend time earning a living, learn sports, take vacations. We waste them in blocks of time called television shows instead of activities that feed our soul and burn some calories.

And then there was you, Jenny. Keeping each morsel you bought and made for your children, reminders of your life that you could touch and hold. Living in this house, surrounded by a mountain of memories that remain after you are gone. Now strangers hold your memories in their hands and consider whether or not to spend money on them. They see these things and wonder about the resale value of each item or fill in yet another piece of their collection but through your eyes, these things held the sound of your children’s laughter, their rowdy quarrels, dance rehearsals for your daughter, them moaning when you chided them to finish their chores.

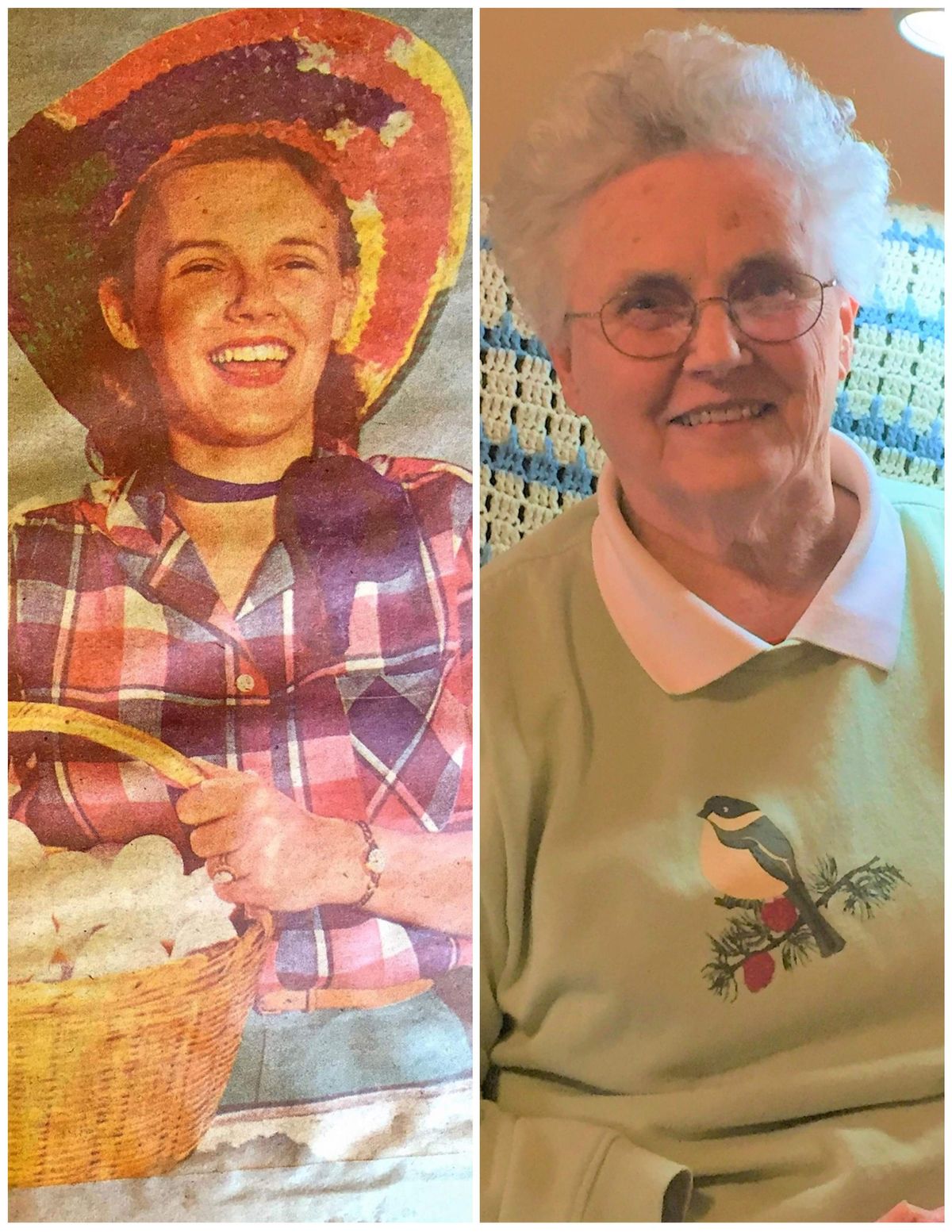

You spent your minutes creating quilts, working far from home to keep food on the table and pay for those dance lessons and Boy Scouts, cross stitching, feeding animals and gathering eggs. I’m imagining those hands, those busy hands that never stilled until you grew old and could no longer do the things you loved to do. And the children who grew up and went away.

You were not a part of their future but you held tight to their past. You’d mesmerize me with your stories of your and their childhoods, historical things of which I could only envision from your description. I still see you smile as you told me your stories.

I miss you, Jenny.